• 1 Breaking Text into Syllables

• 2 Heavy and Light Syllables

• 3 Light Syllables and Holding

• 4 Tonal Accents

• 5 Pronunciation Goals

• 6 The Alphabet and the Cakras

• 7 Sanskrit Meters (Chanda)

Lesson 1: Breaking Text into Syllables

For best results in pronunciation and chanting, we focus on pronouncing syllables (akṣaras) rather than words or phrases. This requires disassembling words, which can be quite long in Sanskrit. A syllable is a single sound produced by the pronunciation of one or more letters (varna), which must include one vowel. There are two steps in cognizing syllables and their meter.

1. Identifying Syllables: The first step in cognizing how to pronounce a word or phrase is to divide it into syllables.

2. Discerning Duration: After splitting syllables we then determine which are heavy (guru, receiving two mātras) and which are light (laghu, one mātra), as we explain in the next lesson. This in turn allows us to pronounce words correctly and experience the rhythmic meter built into mantras and other chants. Meter and its study is called chandas.

Note that these rules, which over time become second nature, apply to general pronunciation as well, not just to chanting.

The Basic Rules for Splitting Syllables

1. A syllable must have one, and only one, vowel: In Sanskrit, two vowels never occur directly alongside each other. If two vowels come together, as when words join in a line, they are combined (by the rules of sandhi) into a semi-vowel and vowel (e.g. hi + at = hyat) or a composite vowel (ha + it = het). In this regard remember that ai and au are diphthong vowels, and although they are written in Roman script as paired vowels, they are actually singular letters in Sanskrit.

2. Every syllable must begin with a consonant if possible, but may end in any number of consonants, so long as the next syllable also can follow this rule as well (meaning begin with only one consonant). For instance, tata would be split as ta + ta, not as tat + a, and rāma splits as rā + ma, not rām + a.

a. A syllable can begin with a vowel if the syllable is at the beginning of a verse or half verse. For example iti will be i – ti, or again etat will be e – tat, at the beginning of a verse or half verse. However, if these were not at the beginning of a verse, their initial vowels would always be amalgamated into the prior syllable. For example, tam + etat + iti will be ta – me – ta – ti -ti.

b. A syllable in the middle of a verse or half verse can begin with a vowel if it follows a consonant that is removed due to a special rule. For example, narāḥ + agni, by sandhi rules, will become narā agni and the syllables will split as na – rā – ag – ni. Here the two vowels of narā + agni remain as separate syllables because the consonant ḥ intervenes and then is removed due to a special sandhi rule.

3. When a sparśa consonant appears (a stop letter or a nasal: e.g., k, kh, c, d, t, n, etc.) after a vowel, the syllable ends with that consonant. This rule clarifies where the break occurs when two or more consonants fall together. For example, if we examine the word mantra without considering rule 2, we could assume that the syllable break would be mant – ra (since that way each syllable is beginning with only one consonant), but rule 3 clarifies that syllables can’t continue past certain letters, in this case the consonant n. So, the first syllable has to stop at the n, and the word is correctly split as man – tra.

4. When an anusvāra (ṁ) or visarga (ḥ) appears, the syllable ends with the anusvāra or visarga. For example saṁtraṇa, will split as saṁ – trā – ṇa; not as saṁt – ra – ṇa. Likewise for visarga ḥ, tejaḥpra is split as te – jaḥ – pra; not as te – jaḥp – ra.

Examples

The syllables of kṛtsnam break as kṛt-snam—not as kṛts-nam—because of the rule that a syllable terminates with the appearance of a sparśa consonant, in this case t. It cannot also include the letter s. Similarly, tvāmahaṁśṛṇomi is correctly divided as tvā-ma-haṁ-śṛ-ṇo-mi, not as tvā-mah-aṁ-śṛ-ṇo-mi.

Three more examples

asato mā sadgamaya …………….. a-sa-to mā sad-ga-ma-ya

tamaso mā jyotir gamaya …………… tamaso mā jyotir gamaya

mṛtyormāmṛtam gamaya…….. …. mṛt-yor-mām-ṛ-tam ga-ma-ya

Tip: don’t be misled by aspirates in transliteration

When splitting syllables, keep in mind that the aspirate letters (kh gh, cha, jha, ṭha, ḍha, tha, daha), are singular sounds even though in Roman script they are made up of two glyphs. So, for instance, abha would break as a-bha, never as not ab-ha. This is obvious in Devanāgari, because each aspirate (e.g. bha = भ) is a single letter form. A-bha = अ / भ.

Exercise 4.1.1

Split the words below into syllables according to the above rules, then check your accuracy against the answer key that follows.

Tatsavitur vareṇyam bhargo devasya annamaya atattva

nandi kārttikeya karma kathā mudrā siddhānta

samādhi garbha avidyā dhyāna sāyujya

—————

ANSWERS

tat-sa-vi-tur va-reṇ–yam bhar-go de-vas-ya an-na-ma-ya

nan-di kārt-ti-ke-ya kar-maka-thā mud–rā sid–dhān-ta

sa-mā-dhi gar-bhaa-vid–yā dhyā-na sā–yuj-ya

Supplementary Video

Enjoy Swami Tadatmananda’s short discussion of meter in his “Introduction to Vedic Chanting” (9:00-10:21)

Lesson 2: Heavy and Light Syllables

In early lessons we learned that there are short vowels and long vowels, hrasva and dīrgha. There are also two types of syllables (akṣaras): light (laghu) and heavy (guru). These two terms, like hrasva and dīrgha, also refer to duration. Heavy syllables take two mātras to pronounce. Light syllables take one mātra (count) to pronounce.

The interplay of light/heavy syllables determines the rhythm, or meter, of pronunciation.

The main rules that distinguish heavy/long syllables.

For simplicity, we will use the terms long and short.

1. A syllable is long if it contains a long vowel.

2. A syllable is long if it ends in a consonant, it is long (even if its vowel is short).

3. A syllable is long if it ends with a visarga or anusvāra.

4. A syllable is long if it is the last syllable of a line (even if its vowel is short) because of the slight pause given between lines of a verse.

5. All other syllables are short.

With a little experimenting you can familiarize yourself with the natural wisdom of these rules. For example, when you say a series of light syllables in a row, you will find you can pronounce them rapidly with no pause (like na na na na na). But to clearly pronouncing heavy syllables of any kind, a certain automatic pause or slow down is required (try nas nas nas… compared to na na na…).

Take the word tattva. It is split as tat-tva. if we distinctly enunciate each syllable, heaviness of the first syllable is unavoidable. A good proof for this is to modify the spelling of the word slightly, so as to change the syllable weight. Thus, compare: tat + va (heavy + light), ta + tva (light + light) and tat + tvā (heavy + heavy).

Exercise 4.2.1

Distinctly enunciating each syllable is essential to good chanting. A helpful practice for learning a chant correctly is to write or type it yourself with the syllables split. Insert a hyphen to show syllable breaks, but not between words. Make the heavy/long syllables bold (or use a highlighter) to distinguish them from the light/short syllables. Below are three examples. Study these to see how the rules of guru and laghu have been applied.

asato mā sadgamaya |

a-sa-to mā sad-ga-ma-ya |

tamaso mā jyotir gamaya |

ta-ma-so mā jyo–tir ga-ma-ya |

mṛtyormāmṛtam gamaya |

mṛt–yor–mā-mṛ-tam ga-ma-ya |

————————————

prasannasyandanojjvalām

pra-san–nas-yan-da-noj-jva-lām

————————————

om bhurbhuvaḥ suvaḥ |

om bhūr-bhu-vaḥ su-vaḥ |

tatsavitur vareṇyam |

tat-sa-vi-tur va-reṇ–yam |

bhargo devasya dhīmahi |

bhar–go de–vas-ya dhī-ma-hi |

dhiyo yo naḥ pracodayāt ||

dhi-yo yo–naḥ pra-co-da-yāt ||

Exercise 4.2.2

Here we practice breaking words into syllables according to the rules in lesson one, then determine which syllables are heavy and which are light, according to the rules in lesson two. If you are on a desktop computer, you can copy/paste the sample words below and insert hyphens to indicate syllable breaks. When you finish check your answers against the answer key that follows.

tatsavitur vareṇyam bhargo devasya annamaya atattva

nandi kārttikeya karma kathā mudrā siddhānta

samādhi garbha avidyā dhyāna sāyujya

ANSWERS

tat-sa-vi-tur va-reṇ–yam bhar-go de-vas-ya an-na-ma-ya

nan-di kārt-ti-ke-ya kar-ma ka-thā mud–rā sid–dhān-ta

sa-mā-dhi gar-bha a-vid–yā dhyā-na sā–yuj-ya

Supplementary Video

Watch Ramesh Natarajan’s “Chanting Rules-03 Chandas” for an overview of meter and syllables.

Lesson 3: Light Syllables & “Holding”

Distinguishing heavy/long and light/short syllables is usually done by assessing which are long, but an alternate and simpler method is to discern which are short. A syllable is short if and only if it ends in a short vowel (a, i, u, ṛ or ḷ). In all other cases, a syllable is heavy. For example, the three syllables in red in the following line are light, as they each end in a short vowel.

tat sa–vi-tur va-reṇ-yam

One exception is that a syllable is long if it is the last syllable of a line (even if its vowel is short). In Devanagari, line endings are marked by a single vertical line: |. The final line of a verse is marked by a pair of vertical lines: ||. These same punctuation symbols are often used in Roman transliteration as well.

Beware: It is common for Sanskrit chants to be broken into half lines for ease of reading, but the syllables ending half lines are not supposed to be heavy. However, chanting groups sometimes do develop a style of pausing at the end of half lines, effectively making their final syllables heavy.

Since there are many ways a heavy syllable can occur, and just one way that a syllable can be light, you may find is easier to pick out the light syllables. You then know that all others are heavy. In practice, you may find yourself using both methods. Over time, the rules will become second nature.

Holding

When a consonant joins with a succeeding consonant (or consonants), they form a conjunct. This means that the first consonant becomes a “half letter” (as it has to drop its inherent vowel to join with its partner). For example, examine the word siddhānta. It has two conjuncts (marked in bold siddhānta): ddh and nt. These are also points of syllable division: sid / dhān / ta.

As explained in lesson one, any syllable ending in a consonant is a long syllable, meaning it is held for two mātras. This extenuation is a natural result of fully sounding the closing half letter. Actually, the half syllable does not by itself take up to full mātras, but the sound is lingered on briefly to complete two mātras so as to maintain meter.

A common pitfall is to rush through conjuncts and not enunciate the half letters. Thus, for example, we often hear the word siddha pronounced as if it were spelled sidha. Giving ample time to the first half of a conjunct and clearly enunciating its closing half letter—an is an essential feature of correct chanting—is called “holding.”

Advanced: Duration of Guru Syllables

In this course, we follow the system used for mātra-based meters in which all dirgha syllables are given two mātras, equal in length to a syllable with a long vowel. That this system is well established is evidenced by the fact that the Totaka meter used by Adi Shankaracharya is set to beats and music following the rule that a laghu syllable is one count and all guru syllables are exactly two. There are also other approaches in which heavy syllables that do not contain a long vowel are given a more nuanced time for pronunciation.

Supplementary Video

Here Ramesh Natarajan offers insights on the practice of holding.

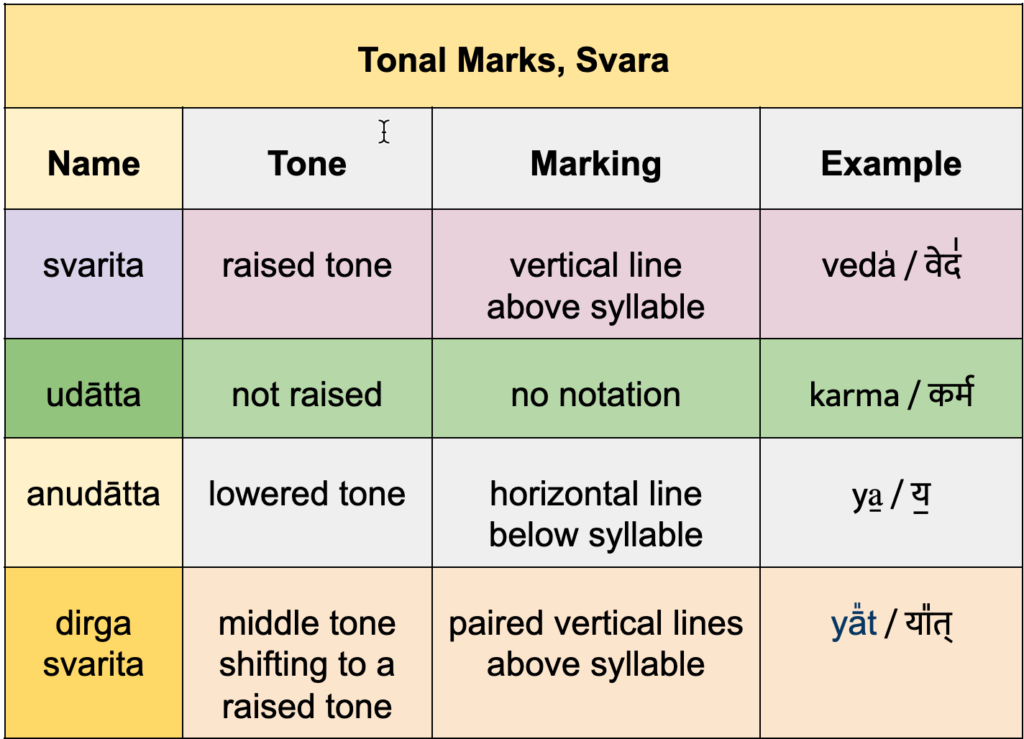

Lesson 4: Tonal Accents, Svara

Tonal notes, or svaras, found in ancient Sanskrit texts such as the Vedas, guide chanters to infuse melody and poetic emphasis into the verses. The realm of svaras is highly complex. Here we introduce the four main svaras, which are found in several of the mantras presented in this course.

Variation in the Use of Svaras

The different branches, or śākhās, of the Vedas have unique manuals dictating how they preserved perfect pronunciation. These manuals are called prātiśākhyas or pārṣadas, depending on the Vedic school they hail from. Along with a host of other pronunciation guidelines, the manuals contain the procedures that determine when and where the svaras are placed according to the rules of sandhi.

No Syllabic Stress in Sanskrit In speaking English, stress is used to emphasize one syllable over another. For example, in the word photographic, the third syllable is stressed: /pho-to-GRA-phic/. Spoken Sanskrit does not stress one syllable over another.

Supplementary Video

For a concise presentation of the svaras, watch Swami Tadatmananda’s

“Introduction to Vedic Chanting” (time: 0 to 4:25 min.)

Supplementary Video

In “Chanting Rules—08—Vedic Swaras (Krishna Yajur Veda),” Ramesh Natarajan discusses swaras and gives a technique to master them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZJIH609nNPw&t=1177s

Lesson 5: Pronunciation Goals

- correct pronunciation of all akṣaras

- correct observance of anusvāra and visarga

- careful adherence to meter to keep an even rhythm throughout the chant. This is accomplished by…

- correct splitting of syllables

- attention to vowel duration (hrasva/dīrgha/pluta)

- attention to guru (heavy/long) and laghu (light/short) syllables, including attention to “holding”

- expertise in accents for Vedic chants (dātta, anudātta and svarita, etc.)

Supplementary Video

To ensure continual improvement in your chanting,

watch and take to heart Ramesh Natarajan’s “Tips for Practicing.”

Tip: No Syllabic Stress in Sanskrit

In speaking English, stress is used to emphasize one syllable over another. For example, in the word photographic, the third syllable is stressed: /pho-to-GRA-phic/. Spoken Sanskrit does not stress one syllable over another.

Lesson 6: The Alphabet and the Chakras

Taking the forty-eight common letters of the Sanskrit alphabet and adding the long vowel ḹ (rarely used) and the conjunct letter kṣa gives a total of fifty Sanskrit letters. The six cakras from the mūlādhāra to the ājñā have a total of fifty petals. The following is the correlation between them, given below, according to ancient texts. All the letters are written with ṁ (anusvara), denoting them as bijas. The correlation begins in the viśuddha cakra and comes down one cakra at a time to the mūlādhāra.

Ājñā Cakra, Two Petals

Sanskrit letters: kṣaṁ and haṁ.

The letter haṁ is written in white on the ājñā cakra’s left petal and represents Śiva, while the letter kṣam is written in white on the right petal and represents Śakti.

Viśuddha Cakra, Sixteen Petals

aṁ — āṁ — iṁ — īṁ — uṁ — vūṁ — ṛṁ — ṝṁ — ḷṁ — ḹṁ — eṁ — aiṁ — oṁ — auṁ — aṁ — aḥ.

Anāhata Cakra, Twelve Petals

Sanskrit letters: aṁ — khaṁ — gaṁ — ghaṁ — ṅaṁ — caṁ — chaṁ — jaṁ — jhaṁ — ñaṁ — ṭaṁ — ṭhaṁ.

Maṇipūra Cakra, Ten Petals

ḍaṁ — ḍhaṁ — ṇaṁ — taṁ — thaṁ — daṁ — dhaṁ — naṁ — paṁ — phaṁ.

Svādhiṣṭhāna Cakra, Six Petals

baṁ — bhaṁ — maṁ — yaṁ — raṁ — laṁ.

Mūlādhāra Cakra, Four Petals

Sanskrit letters vaṁ — śaṁ — ṣaṁ — saṁ.

Exercise 4.6.1

While listening to the audio file, read the letters of each cakra as written above.

Lesson 7: Sanskrit Meters (Chanda)

Chandas names the poetic metering of Sanskrit chants. Most meters are based on a specific number of syllables per verse. Some meters, however, include other features, like specific combinations of light (short) and heavy (long) syllables.

The vast majority of Sanskrit verses are written with meter. Learning about meter helps us understand the structure, rhythm and even the proper grammar of Sanskrit verses. There are many meters in Sanskrit, but seven are considered to be major: Gāyatri, Uṣhṇih, Anuṣthubh, Bṛhati, Paṅkti, Triṣtubh and Jagati. These seven are all syllable based, with no consideration of syllable duration. Many of these seven are found in Vedik chants, with four being most common:

Gāyatri: 24 syllables (3 sections of 8 syllables each)

Anuṣṭhubh: 32 syllables (4 sections of 8 syllables each)

Triṣṭubh: 44 syllables (4 sections of 11 syllables each)

Jagati: 48 syllables (4 sections of 12 syllables each)

Since most meters are broken into sections (and the most common meters are broken into even numbers of sections), segmenting long complex lines of Sanskrit. Let’s look at an example, try counting the syllables in the following verse, and then continue to the next page:

aum an-na-pūr-ṇe sa̱-dā-pūr-ṇe śa̱ṅ-ka-rap-rā-ṇa-val-la-bhe |

jña̱-na-vai̱-rāg-ya̍ si̱d-dhyar-tha̍m bhi̱k-ṣām de̱-hi ca pā̍r-va-tī ||

This mantra is in the meter Anustubh, which has 32 syllables (the oṁ/aum is generally not counted as a syllable in mantras and verses). Though there is only a true pause in chanting when a line or double line appears (| or ||), the 32 syllables can be split into four quarters of 8 syllables (as shown below) for easy reading:

oṁ

annapūrṇe sa̱dāpūrṇe (no pause)

śa̱ṅkaraprāṇavallabhe |

jña̱navai̱rāgya̍ si̱ddhyartha̍m (no pause)

bhi̱kṣām de̱hi ca pā̍rvatī ||

an na pūr ṇe sa̱ dā pūr ṇe (no pause)

śa̱ṅ ka rap rā ṇa val la bhe |

jña̱ na vai̱ rāg ya̍ si̱d dhyar tha̍m (no pause)

bhi̱k ṣām de̱ hi ca pā̍r va tī ||

For longer meters, chanters often write them with a split at the quarter points of verses for easier reading. However, in the original texts, the only breaks are end of line (|) and end of verse (|); no other visual breaks are provided.

Exercise 4.7.1

See if you can discern the number of syllables in the following verses. Do this by writing each verse by hand, or digitally (copying the text from this page), inserting hyphens breaks between syllables. The correct result is shown below.

……………. 1 ………………

gaṅge ca yamune caiva

godāvari sarasvati |

narmade siṅdhu kāveri

jalesmin sannidhim kuru ||

……………… 2 ……………..

oṁ ekadantāya vidmahe

vakratuṇḍāya dhīmahi |

tanno danti pracodayāt ||

………………. 3 …………….

oṁ śuklāmbaradharaṁ vishṇuṁ

śaśivarṇaṁ caturbhujam |

prasannavadanaṁ dhyāyet

sarvavighnopaśāntaye ||

………………. 4 …………….

oṁ gaṇānāṁ tvā gaṇapatiṁ havāmahe

kaviṁ kavīnāmupamaśravastamam |

jyeshṭharājaṁ brahmaṇām brahmaṇaspata

ā naḥ śṛṇvannūtibhiḥsīdasādanam ||

ANSWERS

Chant 1: gaṅge ca… — 32 syllables – 4 sections of 8

Chant 2: ekadantāya… — 24 syllables – 3 sections of 8

Chant 3: śuklām… — 32 syllables – 4 sections of 8

Chant 4: gaṇānāṁ… — 48 syllables – 4 sections of 12

For more on Chandas, see:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanskrit_prosody

An informative quote from the above article:

“In addition to the syllable-based metres, Hindu scholars in their prosody studies, developed Gana-chandas or Gana-vritta, that is, metres based on mātrās (morae, instants). The metric foot in these are designed from laghu (short) morae or their equivalents. Sixteen classes of these instants-based metres are enumerated in Sanskrit prosody, each class has sixteen sub-species. Examples include Arya, Udgiti, Upagiti, Giti and Aryagiti. This style of composition is less common than syllable-based metric texts, but found in important texts of Hindu philosophy, drama, lyrical works and Prakrit poetry. The entire Samkhyakarika text of the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy is composed in Arya metre, as are many chapters in the mathematical treatises of Aryabhata, and some texts of Kalidasa.”