• 1 The Consonants, Vyañjana

• 2 Grouped Consonants

• 3 Ungrouped Consonants

• 4 Aspiration, Prāṇa

• 5 Voicing, Ghoṣa

• 6 Subtleties of Voicing & Aspiration

• 7 Logical Structure of the Vargas

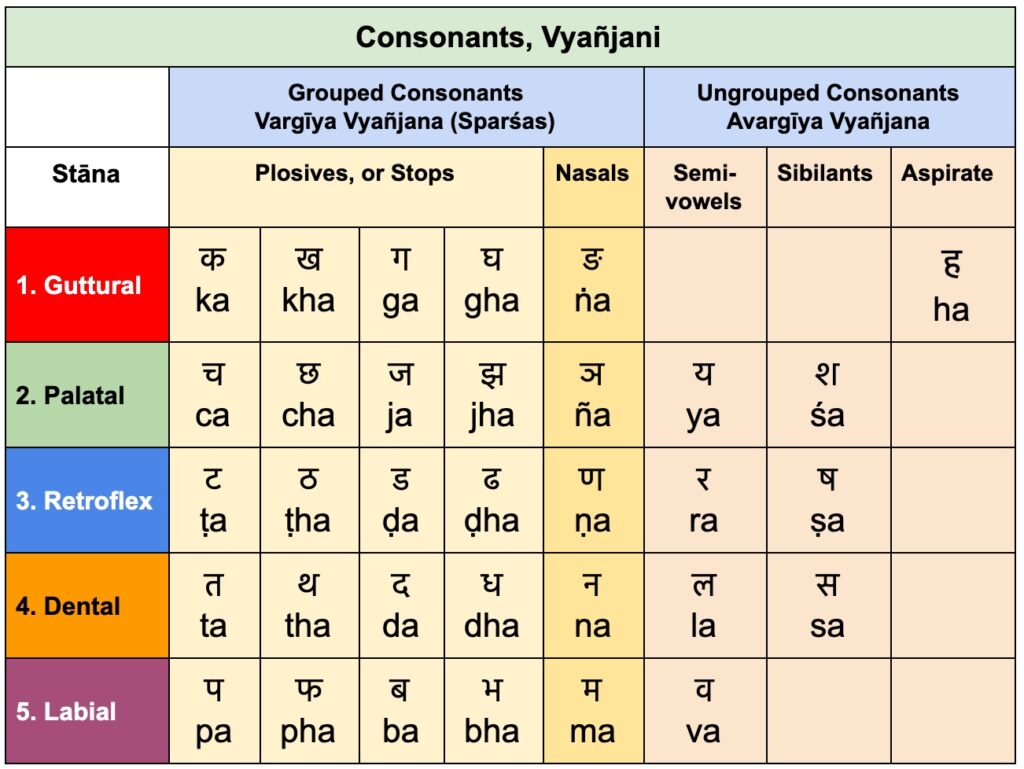

Lesson 1: The 33 Consonants, Vyañjana

Having become familiar with the thirteen vowels, let’s now delve into the consonants. The table below shows the whole collection. These akṣaras, numbering 33, are of two types:

1) grouped consonants (columns 2-6)

2) ungrouped consonants (columns 7-9)

Exercise 2.1.1: Learning the Chart of 33 Consonants

Copy the above chart of all the consonants several times on paper with all the categories and headings. (You may write the akśaras in Roman script only if you do not know Devanāgari.) As a next phase, practice recreating the chart from memory.

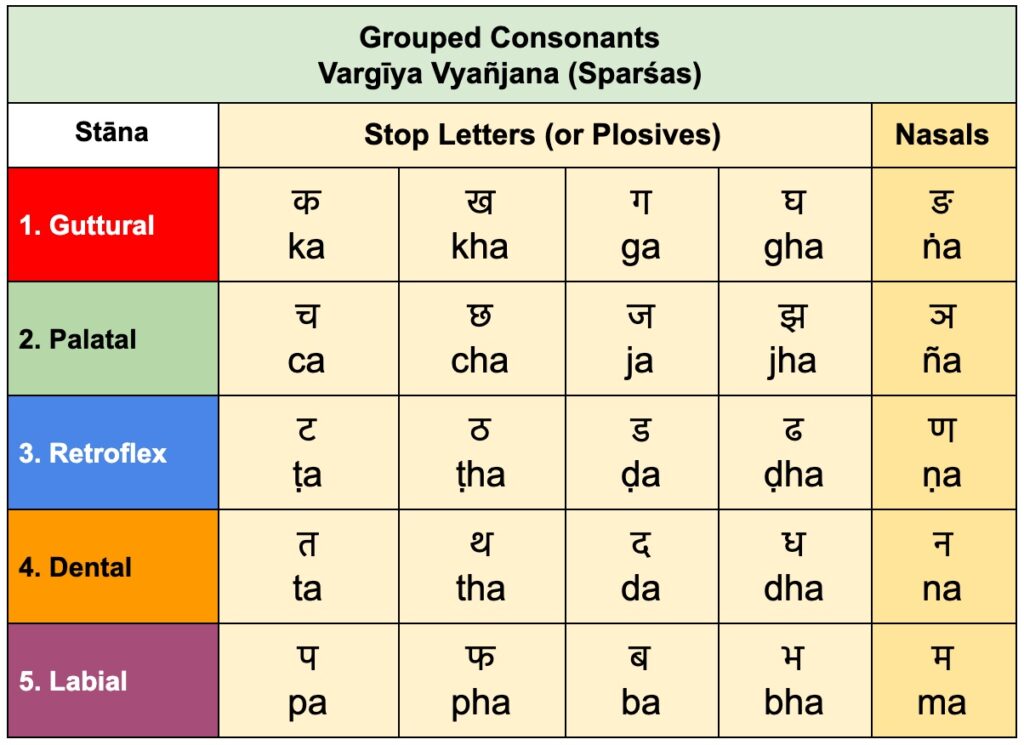

Lesson 2: The 25 Grouped Consonants

Grouped Consonants, Vargīya Vyañjana (25)

The grouped consonants, 25 in number, are classed as sparśas, meaning “touch” sounds. They are of two types: stop letters, and nasals.

Stop Letters (20)

These twenty akṣaras use a full “touch” of the tongue (or lips) to stop the flow of air in the mouth as part of their pronunciation. The chart above shows the 25 stop letters (or plosives)

क ka

च ca

ट ṭa

त ta

प pa

ख kha

छ cha

ठ ṭha

थ tha

फ pha

ग ga

ज ja

ड ḍa

द da

ब ba

घ gha

झ jha

ढ ḍha

ध dha

भ bha

1. guttural

2. palatal

3. retroflex

4. dental

5. labial

Nasals (5)

The five nasal letters use a full “touch” of the tongue or lips to stop the flow of air in the mouth, while also redirecting the air through the nose. With the nasal letters, the closure at the place of pronunciation is not released, and hence most of the air passes through the nose. The nasal sound is formed by narrowing the air passage at the guttural area. These are the nasal letters:

1. guttural ṅa

2. palatal ña

3. retroflex ṇa

4. dental na

5. labial ma

In-depth: How Many Akṣaras Are There in the Varṇamālā?

While in this course we list 49 Sanskrit basic akṣaras, you will see in various texts a count of 50 or 51— reached by the inclusion of the common compound kṣa क्ष and the obscure letter ळ, which rarely appears except in Vaidika texts as a specific sandhi for ḍa ड.

Exercise 2.1.2: Learn the Grouped Consonant Chart by Heart

Copy the Grouped Consonant chart (above) by hand several times on paper with all the categories and headings. (Write the akśaras in Roman script only if you do not know Devanāgari.) Train yourself to create the chart from memory.

Lesson 3: The Eight Ungrouped Consonants

The ungrouped consonants (gray columns), like the nasals, are also non-touch consonants. They consist of four semivowels, three sibilants and the aspirate (ha ह).

With these three sets of letters, the flow of air is restricted but not stopped in the course of pronunciation. In other words, the tongue does not momentarily stop the flow of air as it does with the grouped consonants, or sparśa letters.

To experience the difference between a non-touch akṣara and a stop akṣara, compare the pronunciation of ta, which is a stop letter (the tongue touches the back of the front upper teeth), to sa, which is not a stop letter (the sound is restricted by the tongue near the teeth, but not stopped).

The Four Semivowels

Sanskrit has four semivowels (or approximates): ya, ra, la and va. Like the vowels, the semivowels require the use of the vocal cords. For each semivowel, the tongue (or lips) come near one of the points of pronunciation in the vocal system, restricting the flow of air, but not fully blocking it.

य — ya — palatal — (position 2)

sounded at the roof of mouth, with the tongue held down

र — ra — retroflex — (position 3)

sounded at the roof of mouth above and behind the teeth

ल — la — dental — (position 4)

sounded with the tip of tongue at the back of front teeth

व — va — dental/labial — (positions 4 & 5)

sounded at the teeth and lips

The Three Sibilants

There are three sibilants in Sanskrit: śa, ṣa and sa. Each of these letters, like the semivowels, is pronounced by bringing the tongue near its point of pronunciation in the mouth, restricting the flow of air, but not fully blocking it. These letters are characterized by their hissing sound. The vocal cords are not used in their pronunciation. When properly pronounced, each is clearly distinguishable.

śa — श — Palatal — (position 2)

sounded at the roof of mouth, with the tongue held down

ṣa — ष — Retroflex — (position 3)

sounded at the roof of mouth just behind the teeth

sa — स — Dental — (position 4)

sounded with the tip of tongue behind the upper front teeth

Supplementary Video: Introducing the Consonants

Exercise 2.3.1: Learn the Ungrouped Consonants

Copy the Ungrouped Consonant chart by hand several times on paper with all the categories and headings. (Write the akśaras in Roman script only if you do not know Devanāgari.) Train yourself to create the chart from memory.

Exercise 2.3.2: Learn to Pronounce the Consonants

Following along with the audio, repeat the following sequence of consonants slowly, being mindful of the difference in feel of the articulation points and the way the different parts of the tongue touch the spaces inside the mouth. Notice how the ungrouped sounds feel softer in the mouth because they are non-touch consonants. Repeat these sequences over and over. Work on them again and again to learn their correct pronunciation.

1) The four semivowels: ya, ra, la, va

First, with the audio, listen and practice the correct pronunciation of each of these four letters.

Second, compare how ya and ai, ra and ṛ, la and ḷ, va and au feel in the mouth

(each semivowel paired with a vowel of the same position).

2) The three sibilants: śa, ṣa, sa

Listen to the audio closely to discern each sibilant’s point of articulation:

śa (palatal), ṣa (retroflex) and sa (dental).

3) The aspirant: ha ह

Note that this akṣara is sounded from the guttural position, no. 5.

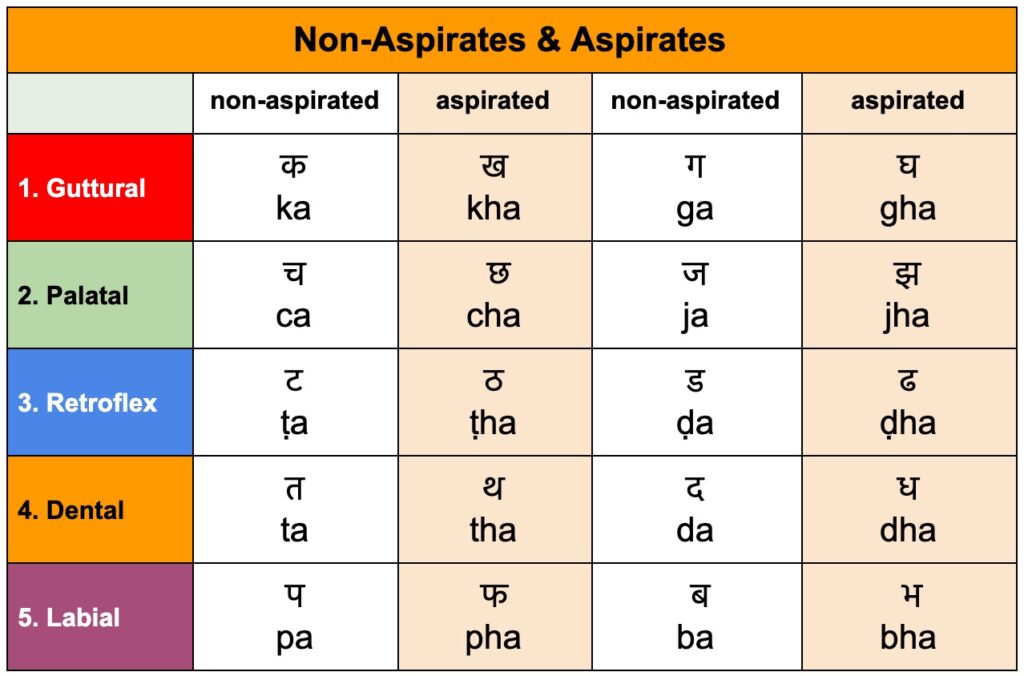

Lesson 4: Aspiration, Prāṇa

In Sanskrit, ten akṣaras are sounded with an extra force of air; for example kha. This force of air is called aspiration. Thus, these letters are known as aspirates, or mahāprāṇa in Sanskrit.

The ten consonants with minimal air behind them (like ka) are classed as unaspirated, or alpaprāṇa. These ten akṣaras are the basis for the aspirated akṣaras. In other words, the ten fundamental stop consonants are unaspirated (columns 2 and 4). Each has an aspirated version (columns 3 and 5).

Aspirates are pronounced with full breath.

Non-aspirates are pronounced with minimal breath.

Note: In Roman transliteration, aspiration is indicated by the letter h after the base consonant, as shown in the two tan columns above. For example, kha. In Devanāgari, as you can see in the table, the aspirated forms are entirely different glyphs.

Exercise 2.4: Practicing Aspiration

Listen closely as the teacher enunciates the words in the following list. Repeat each word after it is spoken, mimicking his pronunciation closely. Notice where your tongue goes as you say the words. As you listen closely and practice the words, pay close attention to how the sounds, the force of air (aspiration) and positions of the tongue differ.

adhyātma

advaita

ardhanārīśvara

ārdrā

atharva

ātman

dharma

paddhati

tīrthayātrā

tripuṇḍra

ghana

khaḍga

chanda

rūḍha

phala

bhakti

darśana

pada

jhirikā

paṭha

Lesson 5: Voicing, Ghoṣa

All of the consonants can be distinguished as either voiced or unvoiced. (Note that all vowels are voiced.) Other terms used for voicing are soft (for voiced) and hard (for unvoiced). Voiced (saghoṣa) letters use the vocal cords. Unvoiced (aghoṣa) letters do not use the vocal cords; these sounds are made primarily by air simply passing through the mouth. The prime example of an unvoiced consonant is ka.

The voiced letters occupy the blue columns in the table. Unvoiced letters are in the yellow columns.

You can feel the difference between a voiced letter and an unvoiced letter if you hold your fingers to your Adam’s apple during pronunciation. Compare ka with ga. With your fingers, you can feel the vocal cords vibrate when you pronounce ga. With the sound ka there is no vocal cord resonance. To feel the difference more easily, compare ak to ag.

This distinction between voiced and unvoiced letters is an essential part of understanding the structure of the Sanskrit alphabet. Voicing plays an important role in the principle of sandhi, the way certain letters coming together in speech change one another. Though these changes occur in all languages, Sanskrit, with its fully phonetic writing system, is unique for formalizing the changes in the spelling and writing of words.

To get an idea of how the voicing of one letter can influence another, try comparing the final s sounds of the plural english words cats and dogs. Notice that the s in cats sounds like a normal s, whereas the s in dogs sounds and vibrates like a z sound. This change occurs because the s in dogs follows the voiced/soft letter g, which activates the vocal cords. This activation of the vocal cords for the letter g affects the letter s, making it voiced as well, and changes its sound to that of z. If you try, you may be able to forcibly remove the voicing from the final s in dogs. But if you listen to yourself closely, you will find that either you have added an extra pause between the letters or you have ended up actually saying doks. In other words, to keep from adding voicing to the letter s, you have removed the voicing from the proceeding g, thereby producing its unvoiced counterpart, which is k.

To ascertain if any letter is voiced or unvoiced, try prolonging the initial sound of the letter (like the gggga or kkkka) before releasing the vowel after it. In the case of a voiced letter, like g, you will feel a vibrating sensation similar to what you would feel while humming. This humming sensation is the activation of the vocal cords. If the letter is unvoiced, like km you will either find it hard to prolong the initial sound of the letter or you will experience a flow of air making a hissing sound.

Exercise 2.5.1: Distinguishing Voicing (no audio)

Go through the consonants below and determine whether each is voiced or unvoiced. Afterwards, check your answers by consulting the table at the beginning of this lesson.

| sa _______ | jha ______ | ka _______ | ṭa _______ |

| ga _______ | ra _______ | kha ______ | ma _______ |

| ca _______ | na _______ | da _______ | pa _______ |

| ja _______ | śa _______ | ḍa _______ | ya _______ |

Lesson 6: Subtleties of Voicing and Aspiration

Pronouncing the unvoiced,

unaspirated consonants: ka, ca, ta, ṭa, pa

A caution to avoid aspirating these letters.

In English, if a word begins with an unvoiced consonant, meaning it does not use the vocal cords—such as k, c, t, ṭ, p—that sound naturally tends to be aspirated. Hence, to correctly pronounce the unaspirated, unvoiced Sanskrit letters, English speakers must restrain the force of air, so that ka, for example, doesn’t sound like kha.

Learning the difference between

unvoiced and voiced akṣaras

At first, ka correctly pronounced may almost sound like ga. Likewise, the other unaspirated unvoiced letters (ca, ta, ṭa and pa) may sound somewhat like their voiced counterparts (ja, da, ḍa and ba). It will take time to hear and understand this subtlety. With practice, the distinctions become clear.

Studying the similarity in sound between the unvoiced unaspirated letters, like ka, and the voiced unaspirated letters, like ga, can also be helpful in learning the correct pronunciation. This can be done by saying ga several times and then attempting to make ka sound as close as possible to that sound.

The reason this works is that the sound ga engages the vocal cords throughout, while ka begins with a sound made only by air (the k part) and then uses the vocal cords for the vowel. If the vocal cords activate the vowel more quickly, it will suppress the breathy sound of the letter, giving us the unaspirated ka. So, another way to think of the unaspirated ka sound is as a very slight or short k with the vowel sound following quickly after it. This is true for all of the unvoiced unaspirated letters (ka, ca, ṭa, ta, pa).

For the examples in the following lessons on the vargas, words have, when possible, been chosen in which the unaspirated letters are preceded by another letter (for instance, skate rather than Kate). With these added letters, it is more natural to say the unvoiced unaspirated consonants in an unaspirated way.

Aspirated Consonants: gha, jha, ḍha, dha, bha

For the five voiced aspirated consonants (gha, jha, ḍha, dha, bha), the issue is reversed. In Sanskrit, these syllables are aspirated, whereas In English, they are naturally spoken without aspiration (e.g., ga instead of gha). English speakers will have to use the combined words given (e.g., dog-house, in the lesson on Ka varga) to help them realize how to make these sounds properly. Take care to not drop the aspiration from these letters.

Exercise 2.6.1: Practicing Voicing

Listening to the recording, study the difference in the sound of each pairs of letters below. Practice reciting the syllables the sounds along with the speaker.

Note that the first two columns are unvoiced (hard).

The second two columns are voiced (soft).

Strive to the difference between the two.

ka

ca

ṭa

ta

pa

kha

cha

ṭha

tha

pha

ga

ja

ḍa

da

ba

gha

jha

ḍha

dha

bha

Exercise 2.6.2: Voicing with Other Vowels

In this exercise, the voiced and unvoiced letters have been mixed, and different vowels have been introduced. As you listen to the audio, and chant along, work to clearly distinguish the voiced and unvoiced syllables. Record your findings, such as by highlighting the voiced letters. Afterwards, check the answer key below. Observe the vocal chords vibrate more when sounding the voiced syllables.

kī — khu — ghai — gau — chū — cu — ju — jha —ṭā — ṭha

ḍau — ḍho — te — thai — dhe — do — bū — bhī — phi — pa

Answer key (voiced letters are in bold)

kī — khu — ghai — gau — chū — cu — ju — jha —ṭā — ṭha

ḍau — ḍho — te — thai — dhe — do — bū — bhī — phi — pa

Lesson 7:

The Logical Structure of the Vargas

You can accelerate your learning of the sounds of Sanskrit by understanding the structural uniformity built into all the five vargas. Here we show this pattern in the Ka Varga. These principles apply to all five families.

- By simply adding air, we derive kha, the second letter in the family.

- If we soften ka and let the vocal cords vibrate, we derive ga, the third letter of the family. The softening of the sound through vocal resonance is known as voicing, which we will soon learn more about.

- Adding air to ga, we derive gha, the fourth letter of the family. This addition of air is called aspiration. Gha is the aspirated form of ga.

- By nasalizing ga, we derive ṅ, the fifth letter of the family, the nasal. We can derive the proper nasal sound for ourself, by picking a word we know that has an n before the first letter in the varga (in this case k), such as link. Practice pronouncing the ṅk again and again, and then drop off the k sound to isolate to the nasal sound. That is the correct nasal sound for the Ka Varga.

Exception: Of course, for the Pa Varga, the nasal is m, not n.

Exercise 2.7.1: Studying the Varga Pattern

Follow along with the audio as the speaker goes across the five families of letters (horizontally) in the table. As you follow along, listen to how the various features of sounds (voicing, aspiration, etc.) modify the initial sound of the varga as we go across the table. Observe the subtleties of aspiration, voicing and nasalization—a pattern that persists within each of the five families.

Exercise 2.7.2: All Five Vargas

Play the above audio and follow along. This audio goes down the columns of the above table instead of across the rows. The result is five sounds of separate vargas which have the same qualities (voicing, aspiration, etc.), only differing in the position of tongue and lips. Notice also how the point of pronunciation (stana) moves one step forward, from the guttural all the way to the labial, each time we recite one set of five.